How Saudi Arabia Reignited My Love of the Middle East—and Changed Everything

AlUla, Saudi Arabia: the ruins of the ancient city of Dadan stand in front of the lush oasis, against a backdrop of breathtaking sandstone rock formations

“We can have in life but one great experience at best, and the secret of life is to reproduce that experience as often as possible.” – Oscar Wilde

If you can blame anyone for my lifelong fascination with the Arab world, it would have to be my parents.

I grew up hearing countless stories of the years they spent in the region—in Saudi Arabia, specifically—and as a child, I would often sneak into my mother’s closet and try on her black abaya with the fine gold trim, stumbling over the long, draping fabric as I ambled about in front of the mirror.

Then, when I was 16, my parents took me and my brother on a holiday to France and Spain—a trip that unfortunately coincided with the Madrid train bombings. With Spain’s capital city plunged into mourning, my parents made a spontaneous decision to take us to Morocco for a quick day trip, where we ended up visiting Tetouan for several hours before returning back to Algeciras by way of Ceuta.

There was a moment during that trip to Tetouan, some 20 years ago, that changed everything for me: we were standing around in the medina, near a small square, admiring some local handicrafts, when the call to prayer began to bellow out from mosque speakers across the city. I stood in awe at the bustling energy: the busy, narrow streets packed with people and rugs and leather goods; the hurried movements of passersby; the vibrant expression of a bright-eyed woman who briefly caught my gaze as she shuffled along. All the sights and smells and sounds just coalesced in a way that made me feel invigorated—more alive and more present than I’d ever felt before.

This feeling is something I’m always chasing when I travel: the energy of new places, new sights, new sounds, new tastes. The sensation of awe and wonder when you encounter something truly, utterly novel—something that you know, instantly and instinctively, has just become part of who you are. A new piece of the mosaic.

From that moment, a switch went off in my brain—and I was never quite the same. It was a paradigm shift in my life, and it changed everything.

Four years later, I returned to Morocco for a semester abroad; the following semester, wanting to spend time in a country that was actually in the Middle East (and wanting to gain some exposure to a more widely understood dialect of Arabic), I chose to study in Amman, Jordan.

After graduating from university, I decided to head back to Amman. I assumed I’d spend a year or two teaching and then return to the States for grad school. But grad school never happened—and I never moved back to America.

I’ve been living in the Middle East and North Africa for over 15 years now, and it is often difficult to see the forest for the trees. The wonder I experienced as a wide-eyed teenager tends to get lost in the mundanity of day-to-day life. I hardly register the athan (call to prayer) when it bellows out across the sky; I can wander through a busy souk or market without the slightest feeling of unfamiliarity or novelty; the lyrical cadence of Arabic that once whirred itself into an indistinct hum now sharpens into actual words against my eardrums; all of the once-wondrous sights now blur with the haze of a too-long-exposure captured by shaky hands. Reigniting the awe I once felt in this part of the world requires great awareness and stillness—the kind that tends to elude us in our daily lives.

It is why I travel. It is why I take frequent road trips across Jordan, why I hike, why I climb every mountain or hillside, seeking out every new and unadmired vista. I want to feel the breathless swell. I want to feel the way that 16-year-old girl felt in Tetouan.

And then Saudi happened.

Riyadh’s Bujairi Terrace is one of its newest attractions—a beautiful outdoor space overlooking the historic At-Turaif District, and featuring an enormous selection of dining destinations

I’ll be honest: while my parents’ years in Saudi Arabia may have set the stage for how I ended up making the Middle East my home, I had never given much consideration to visiting Saudi itself.

After all, up until a few years ago, the only possible way for me to visit was on a business visa.

And, if I can be frank, the idea of visiting never really piqued much interest—even in recent years, as the country began to open up to tourism, and as my parents began to urge me to visit. “You have to see Jeddah,” they’d say, and I’d roll my eyes like, yeah, sure, eventually—but I’ve got all these other places on my list that I’d rather get to first.

And then Saudi happened.

Tomb of Lihyan, Son of Kuza: One of the most instantly identifiable monuments at Hegra, the site of an ancient Nabataean city. This tomb belonged to a great Nabataean military general, who unfortunately died abroad and was never buried here; it remains unfinished at the bottom (but offers archaeologists great insights into how the Nabataeans built their tombs)

Or, rather, work happened: over the last two months, I ended up needing to take two separate business trips to Saudi Arabia—specifically, to the town of AlUla, along with one brief stop in Riyadh.

And from that very first visit, every assumption or idea I had about Saudi was completely, entirely flipped on its head.

I should pause from my story here for a moment to share a small goal of mine: this year, I made it my objective to finally hit my milestone 40th country. With my trip to Georgia back in June, I had reached 39—and with a short visit to Norway planned for next month, I was already on track to complete my little challenge.

And then Saudi happened.

AlUla’s Old Town is a stunning labyrinth of mudbrick homes and buildings, occupied continuously from the 12th century CE until the 1980s

There are few places on Earth that retain any semblance of mystery—any opportunity for modern exploration and discovery. Having opened up to tourism just a few years ago, Saudi Arabia is one of the last countries in the world that still feels relatively unexplored by outsiders. And you could be forgiven for assuming that, amidst the vast expanses of desert, there isn’t much to be discovered.

But you would be terribly, terribly mistaken. Today, Saudi Arabia is rapidly finding itself at the nexus of past, present, and future—and I can hardly think of any more exciting place to be.

In the region of AlUla and Khaybar alone, there are more than 170,000 identified archaeological sites of interest, and only the smallest fraction has been excavated. These sites include remnants from the earliest days of humanity up through the 20th century, and cover an enormous expanse of history: the advent of agriculture, the rises and falls of great civilizations, the passage of travelers along ancient trade routes and religious pilgrimages, the artistic legacies of people throughout the ages, and a multitude of diverse ways of life—many of which have been carefully preserved and passed down across centuries.

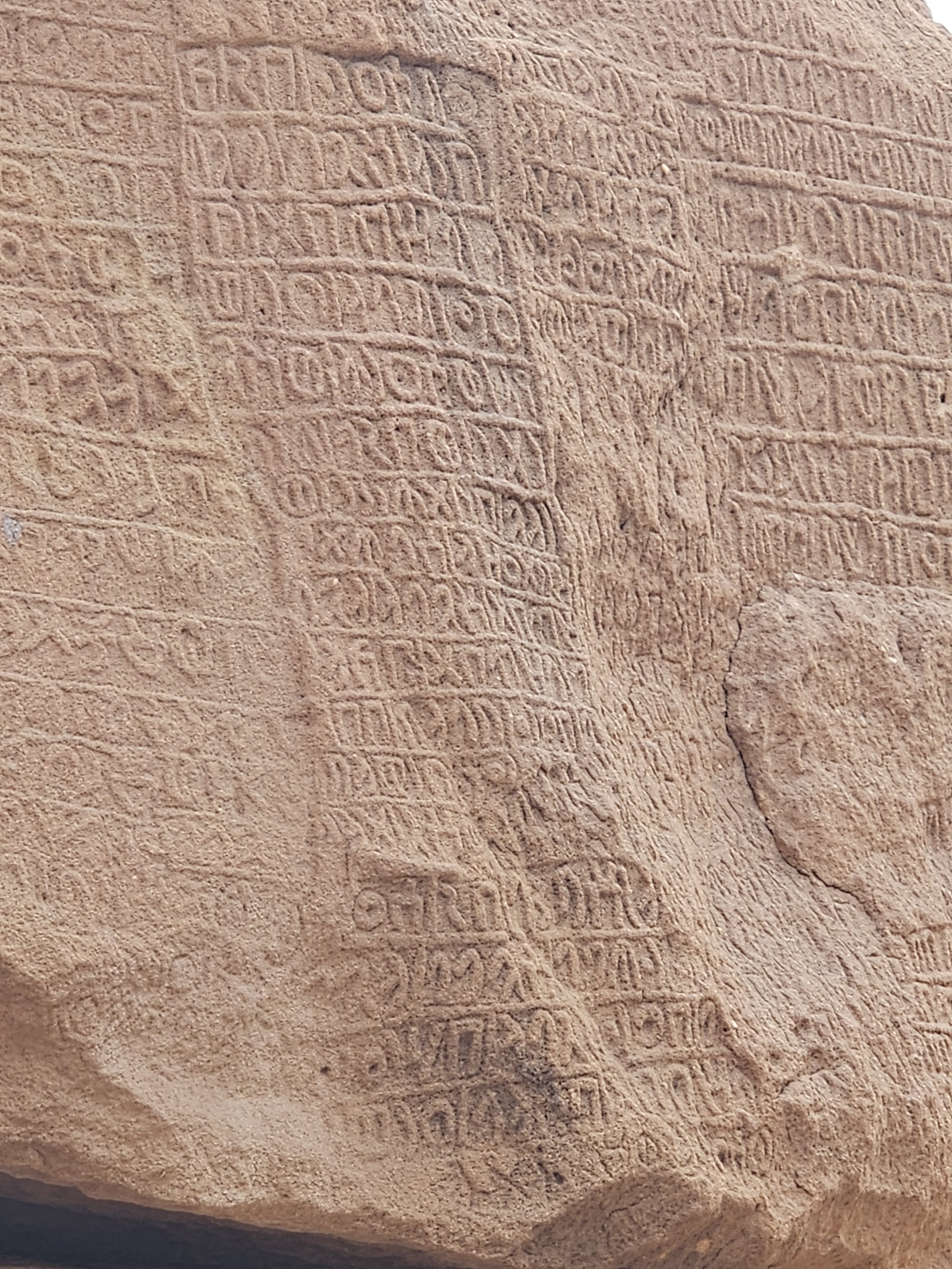

This stone featuring an ancient Dadanitic inscription was repurposed in the wall of a home in AlUla’s Old Town; this layering of the past, in all its multitudes and iterations, can be seen all across the landscape

This captivating oasis once sat along the ancient Incense Road, which stretched from the southern tip of Arabia (in modern-day Yemen) to Egypt, Greece, Babylon, and beyond. Later, with the advent of Islam, it found itself on the pilgrimage route to Makkah. For thousands of years, voyagers passed through AlUla in the midst of long, often perilous journeys through the desert. It was a place of great comfort and endless wonder: the ancient civilizations that once lived there are mentioned in the Bible, in the writings of ancient travelers, and, perhaps most impressively, in inscriptions carved upon the massive sandstone structures that devour the horizon.

The history, yes, is impressive—as is the nature, which is resplendent and breathtaking and surprisingly diverse. Even the accommodation and dining options are superb (I would happily fly to Saudi right now just to have another meal at Somewhere, a restaurant—with branches in both AlUla and Riyadh—that does Arabic and Middle Eastern fusion better than anywhere else I’ve ever known). But what really impressed me about AlUla was the extraordinary vision behind what is rapidly taking shape on the ground.

This vision isn’t just about crafting an exceptional, holistic, and immersive touristic experience (although it does that, too—and does it better than anywhere I’ve ever seen): it’s about sustainably preserving the natural and cultural heritage of a place so jam-packed with historical and cultural and natural wonders that it feels like you’ve stumbled upon Shangri-La or Atlantis. The only difference is that it’s always been here—not hiding, per se, but generally inaccessible to most of the world for much of the last century.

And while I can attest that, generally speaking, Arab hospitality is superb, something about Saudi hospitality just seems to place it in a class of its own: it is a kind of unqualified warmth and kindness and generosity that wants nothing in return.

Exploring Sharaan Nature Reserve, one of five nature reserves in AlUla County, and a wonderful example of the unique local approach to conservation

On my second trip to AlUla, I decided to do a night hike in Sharaan Nature Reserve. After meeting my guide at Pangaea Adventure Club and getting a brief but informative tour of the various types of date palms that grow on their property, we set off for the reserve. The first half of the hike allowed me to soak up the last bit of daylight, reaching our lookout point just as the sun was tipping down into the horizon. Here, we sat and admired the sprawling vista, the rock formations of Hegra set off in the distance. My guide pointed to a large, lone rock formation off to the north of the ancient Nabataean city and regaled me with a story he’d heard from the local tribes, about a man who once lost a baby camel at that very spot. The man circled and circled the rock in vain, calling out for the camel, hearing its cries but unable to find it.

Hiking through Sharaan Nature Reserve, just before sunset

The story, in and of itself, is relatively unremarkable. But spend even the shortest amount of time in Saudi, and you will bear witness to an endless array of local folklore—stories and traditions and anecdotes that have been passed down and preserved for generations upon generations. Now, finally, these stories are finding a more diverse, more global audience. It’s time for them to be heard.

It is easy (and perhaps even a bit lazy) to feel skeptical about Saudi’s recent transformation: to cast a squinty sideways glance at its domestic reforms and immediately start looking for ulterior motives and motivations. But to witness these transformations on the ground, to speak with locals who are watching the world around them develop at break-neck speed, is to restore at least some sense of optimism—to retract some of that skepticism in the earnest hope that it’s all real and sustainable.

Look: I have an innate, knee-jerk aversion to inauthenticity—to anything that feels gimmicky or artificial or commercial. It’s why places like Dubai have never appealed to me: they feel cold and disconnected from any particular culture or tradition, with steel and concrete filling in the wide, vacuous cracks, attempting to crowd out the hollows and displace the utter lack of soul.

The Diwan: This great room, carved into a sandstone rock formation, was once a gathering place for Hegra’s Nabataean citizens

Saudi is nothing like this—despite the fact that I very much expected it to be.

Standing amidst the Nabataean ruins of Hegra, wandering through the narrow canyon of Jabal Ikmah, off-roading through towering rock formations in Sharaan Nature Reserve, admiring Neolithic petroglyphs of ostriches and long-extinct species of cattle, traversing the mudbrick labyrinth of AlUla’s Old Town, gazing up at the lush canopy of date palms in Daimumah—there were so many moments in AlUla when I felt the familiar swell, the voice that stirs and echoes from somewhere deep inside your chest, saying, “This. This is why we travel.”

In Saudi Arabia, you can still feel like a modern Freya Stark—like there are still wonders waiting to be unearthed. And there are—and they are being unearthed so quickly that it feels like you’re sitting at the center of the universe, watching the past, present, and future converge at a single point.

It feels like peeking beyond the event horizon—but instead of a crushing black hole, you find a verdant oasis.

And so, as it turns out, my milestone 40th country has been a milestone in more ways than one: it has helped me rediscover all the sights and sounds and smells that made me fall in love with the Arab world in the first place—while also discovering, for the first time, a country that still feels somewhat undiscovered by the rest of the world.

It reminds me that there is so much left to explore—that wonder still awaits.