Why Luang Prabang is a Morning Lover’s Utopia

The mighty Mekong in the early morning (Luang Prabang, Laos)

I wasn’t always a morning person. As a child, as a teenager, and well into my 20s, I was much more prone to sleeping in. When I was young, I would tumble out of bed and find my younger brother anxiously waiting to announce my arrival to the family. I would stumble and mumble my way out to the dining room for breakfast, unenthused by my brother’s energetic display.

These days, now that he has long been gone from this world, I would give anything to relive those moments. I treasure the memories. I wish I could have appreciated them more when I had lived them. And perhaps that feeling is more just a general characteristic of nostalgia than the nagging regret that comes with loss; perhaps it’s just the longing for childhood that simmers under the surface of all of us. Or perhaps nostalgia is, in fact, a form of mourning—for the past.

Somewhere around my mid-20s, my wake-up time began to gradually shift earlier. Perhaps it was the fact that I stopped going out every night, stopped partying so much, generally just stopped enjoying the late-night frenzy, and began to embrace the quiet solitude of the early morning hours.

(I should also note that I’m not one of those people who can proudly survive on four or five hours of sleep a night: I need a solid eight to nine hours. I will not settle for less unless I’m under extreme duress—or I have an early flight.)

I haven’t set an alarm in years. These days, I rise, naturally, with the sun—which means that I wake up earlier in the summer months and later in the winter. I like to begin my day at a leisurely pace: I’ll get up, make a cup of coffee, and then enjoy it from the comfort of my bed. I’ll read a book, or scroll through Reddit, or flit through Instagram.

Only after my coffee is finished will I get out of bed and officially start my day. These days, that means walking to the gym, working out, walking home, showering, and then heading to the office. On the weekends, my mornings are especially sacred: sometimes I’ll go hiking, sometimes I’ll go have breakfast (or order it in, if the weather isn’t particularly charming), and sometimes I’ll just lounge around with a book, either at home or at a café (my favorite morning café is Rumi, in Amman’s Jabal Weibdeh neighborhood).

Amman, my home, is not a city that rises early, and that’s part of what makes mornings here so alluring: even in the heart of the urban sprawl, it is quiet and peaceful (especially on Friday mornings, before midday prayer).

But nowhere in the world have I fallen more in love with mornings than in Luang Prabang, Laos.

I’ve spoken before on this blog about my obsession with Laos—but I haven’t yet delved into my particular love for Luang Prabang.

It’s one of the most charming places on Earth: the pace of life in Luang Prabang is calm and leisurely, as gentle as a cool summer breeze.

How could you not be completely, utterly charmed by this place?

Luang Prabang was the first city I visited in Southeast Asia, and it remains my favorite. The first time I landed in town, back at the end of 2018, it was near dusk, and the view from the plane window was mesmerizing: the thick canopy-covered mountainsides, lush and verdant, glowed in the last wash of sunlight.

I was in love from that very moment.

It was dark by the time I made it into town, and as the minivan dropped me at the edge of the neighborhood where I was staying, the first thing I noticed was the scent of flowers: jasmine, plumeria, a mélange of floral fragrances clinging to the air.

My accommodation was situated near the banks of the Nam Khan, and as soon as I had checked in and freshened up, I headed straight out to the night market.

I still remember that first bowl of khao soy (noodles with ground pork), that first sip of Beerlao, the sweet coconut pancakes, the quiet nighttime stroll I later took along the Mekong. It was my first taste of heaven on Earth.

Khao soy and a Beerlao in Luang Prabang’s night market (2018)

I don’t remember what time I slept that evening, but I do remember, with great clarity, the way the first rays of soft morning sun peeked through my window. I arose quickly, dressed, and headed out into town.

Luang Prabang comes to a point at the intersection of two rivers: the Nam Khan and the Mekong

I meandered slowly along the banks of the Nam Khan, taking in the general stillness, observing the other early morning souls: a pair of monks. A lone fisherman at the meeting point of the Nam Khan and the Mekong. A small group of Chinese tourists.

Eventually, I made my way to Saffron Coffee, a delightful café along the Mekong: across the street from the café itself, there’s a small seating area that protrudes out over the banks of the river. It’s a heavenly place to relax, sip great local coffee (Laos produces exceptional coffee—especially in the south, along the Bolaven Plateau), and enjoy inimitable views.

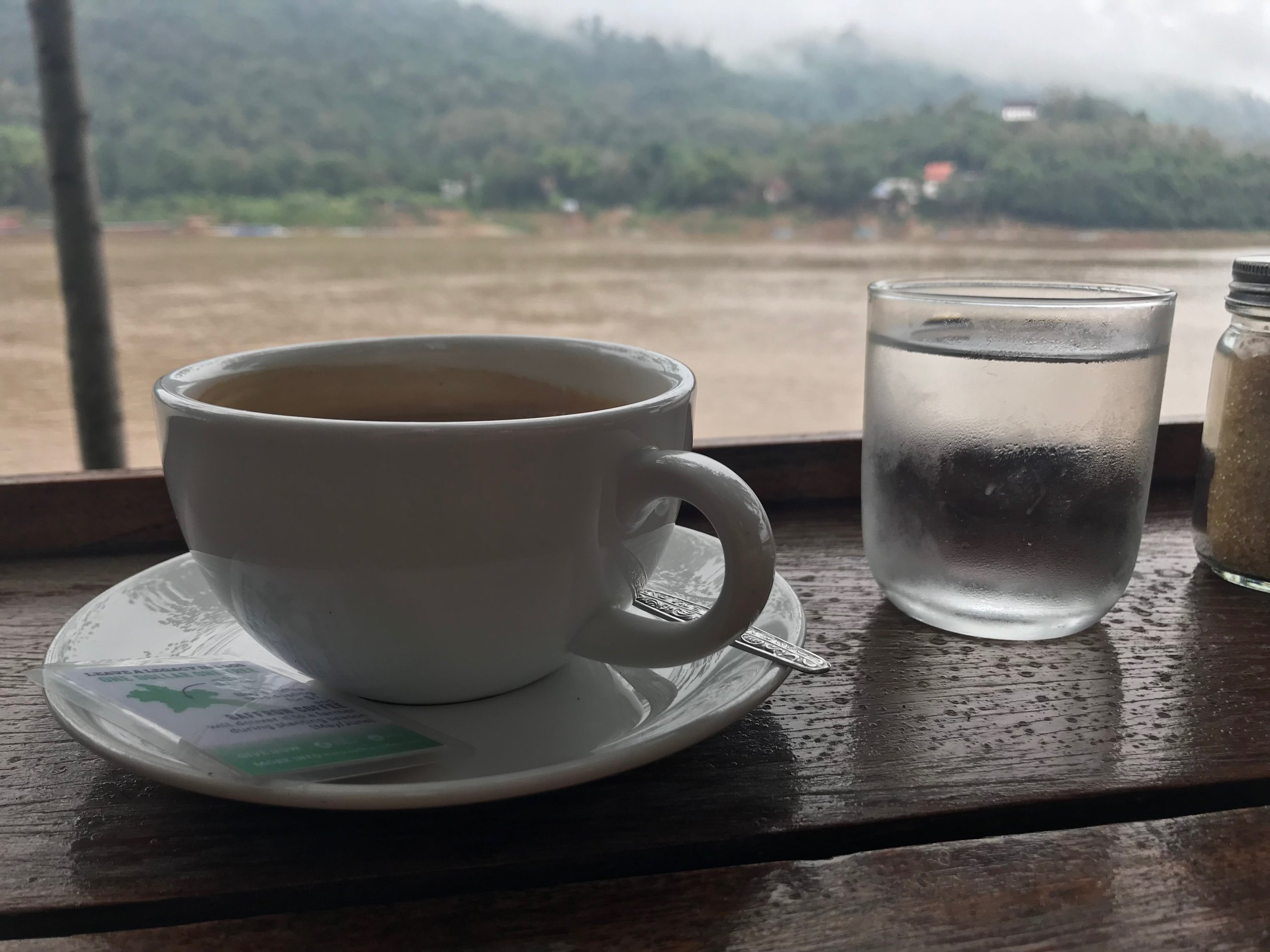

Coffee with a view of the Mekong and the mist-covered mountains in the distance

In the morning, a thick mist clings to the air above the river, obscuring the mountainous backdrop, creating this ethereal, dream-like ambiance; by early afternoon, it has usually cleared.

Each morning of that first trip to Luang Prabang, I would rise early. On my last morning in the city, I woke up while it was still dark and headed straight for the center of town to watch the morning procession of monks. Although a sacred tradition, the morning almsgiving was one of the few things in Luang Prabang that I didn’t particularly enjoy—not because of the tradition itself, but because of the hordes of tourists who flagrantly defy the local customs for observing the procession.

Despite the many signs around town—in multiple languages—explaining the protocols for this daily event (don’t get in the monks’ faces. Don’t follow behind the procession. Keep a respectful distance. Be quiet), there were enough visitors in violation of these rules that I felt I could not justify my own presence. It felt like, simply by being there, I was part of the problem.

I left and wandered over to the morning market, where I once again found magic. Although Luang Prabang is known for its night market (which caters largely to visitors), the morning market feels like a more authentic market experience (although if you want the truly authentic market experience, you need to wake up extra early and head to the outskirts of town, to Phosy Market; it’s a delightful place, with hardly a foreigner in sight).

Taking a tour of the Phosy Market with my hostess, Nee: she and her husband, Si, and his mother gave me a Lao cooking class at their home, and it was one of my all-time favorite food-related travel highlights (not least of all because this lovely family was once featured on the Laos episode of Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown)

The sheer variety of fruits, vegetables, meats, fish, amphibians, and other edible delights is astounding. You’ll also find a few small stalls serving up Lao breakfast essentials: lots of spicy noodle dishes (like my beloved khao soy), khao ji (fried sticky rice), and other culinary mainstays.

A selection of fish at the morning market

It was the perfect way to spend my last morning in Luang Prabang before I caught a bus to Vientiane and continued my Lao adventures.

For four years, I would talk about Luang Prabang with misty eyes, as if my tear ducts still clung to the heavy fog rising off the Mekong. My heart was unsettled: my life decisions suddenly felt all wrong. A few months after that trip, I moved to Morocco—a decision that held felt right before Laos, but after, gave me a nagging sense of regret in the pit of my gut. I had discovered Eden and now I was moving further away from it? I had rediscovered my love of solo travel, of adventure, of independence, and I was going to bind myself to a partner who seemed more inclined to embrace the familiar, the comfortable, the ordinary? Landing in Casablanca a few months later felt like that last scene in The Graduate—the one where they’re sitting in the back of the bus and the smiles on their faces start to drop as the adrenaline and exhilaration wears off, as they begin to reckon with what they’ve done, as the regret sinks in.

I went into a deep depression the year after that first trip to Laos. I could barely get out of bed. I tanked my freelance business, ghosting most of my clients. I cried a lot. I smoked way too much hashish. I would stand in front of the bathroom mirror with my eyes clenched shut, trying, with all my might, to teleport myself through time and space, in the hopes that when I would open my eyes again, I’d be back at my flat in Amman. If that’s not the kind of ‘magical thinking’ that Joan Didion spoke about, then I don’t know what is. I was in mourning. I had lost something vital, and I couldn’t quite put my finger on what it was.

The few joys I felt that year were moments when I managed to get out of Rabat (and away from the life that didn’t feel at all like it belonged to me): a week staying with friends at their farm in the Atlas Mountains, where I picked peas in their garden during the day and doted over their infant daughter in the evenings, and felt like I was half a world away from my problems. A week hiking in the Austrian Alps, under the guise of needing to do a visa run. A one-day visa run to the south of Spain, where I ate Chinese food in Algeciras. Another one-day visa run to the south of Spain, where I ate Chinese food in Tarifa. (Fun fact: southern Spain has great Chinese food.)

It took a global pandemic to shake me out of my depression. It’s a strange thing, but somehow, feeling like the whole world was suddenly experiencing the kind of shut-in isolation I’d felt for the entire year prior was enough to make me feel like I was going to be okay. I felt like the veteran of lockdowns—although the one I’d previously been living in had been entirely self-imposed.

It also made me feel like my location and my predicament was no longer solely my own fault—that now I was stuck for reasons out of my control. It helped me gather the strength to eventually get unstuck.

By mid-2021, I finally made it back to Jordan, and the detour my life had taken sorted itself out. I got my career back on track. I began to travel again. I felt better, happier, and more resilient than ever.

And in January 2023, I finally made it back to Luang Prabang.

My first evening back in Luang Prabang (January 2023)

This time, I had dragged my parents along with me. After hearing me prattle on about Laos for four years like some kind of obnoxious, new-age-y broken record, they were ready to experience this magical country for themselves. And, honestly, I was excited to show it to them.

Our flight landed in the afternoon, and that first day, I took them for a stroll along the Nam Khan and the Mekong, before leading them to the night market and ordering several bowls of khao soy and three bottles of Beerlao.

This particular bowl was actually khao soy ramen: all the normal khao soy ingredients, but with ramen-style noodles instead of the thicker noodles that are traditionally used

We slept fairly early that evening—me, in a room upstairs at our pension, and them, in one of the rooms along the ground floor.

I cannot express the delight I felt when I awoke to the impenetrable darkness of the very early morning, in that precious hour before the sun makes its first appearance.

I stumbled out of bed and threw on my clothes with unimaginable speed, then quietly scurried downstairs and out the door.

I walked briskly along the road, heading exactly where my heart told me to go: the morning market.

The charm of Luang Prabang’s morning market is undeniable

I ordered a bowl of khao soy and sat at a small plastic table, devouring my breakfast with utter relish, and watching as the sunlight began to cascade over the produce-lined alleyway.

By the time I’d finished my noodles, meandered through the market, had a leisurely cappuccino with a view of the Mekong at Saffron Coffee, ordered a couple more coffees to go, and made my way back to the hotel, my parents were just waking up.

As a coffee aficionado, I can confidently say that Lao coffee is some of the best in the world (and don’t you dare come over here prattling on about overrated crap—figurative and literal—like Kopi Luwak)

Their morning was just beginning; mine was already in its second act.

That day, we took a longboat down the river to the Pak Ou Caves, stopping at Lao Lao Whisky Village on the way back. We had lunch that day at Khaiphaen, an incredible restaurant and social enterprise that helps train locals to work in the hospitality sector. Everything we tried was delicious, but it was their superb Beerlao-battered fish and chips that brought us back again the following day.

England be damned: this is the best fish and chips I’ve ever had

In the afternoon, we climbed up to Mount Phousi, meandered through the town, and then my parents went to rest up at the hotel while I wandered off to sip negronis at The Belle Rive Terrace, overlooking the Mekong. My parents eventually met me at the terrace and we enjoyed a few light bites before making our way to the night market once again.

Sai oua (Luang Prabang sausages) and khai paen (local seaweed and rice crackers) at The Belle Rive Terrace

The next morning, having been regaled with my stories from the day before, my parents beat me to it, spending their own morning in the market and returning back with coffee before I’d managed to venture out myself.

That day, we hired a tuk-tuk and drove out to Kuang Si Waterfall, stopping on the way back at Laos Buffalo Dairy for a tour of the farm and a sampling of buffalo ice cream and cheeses. (I plan to dedicate a separate post to this unique project and social enterprise, because it’s worth a deeper dive. I loved it so much, but have slightly mixed emotions about it at the same time; regardless of my strange and confused feelings, I still think it’s well worth a visit, and would wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone.)

A delicious assortment of cheeses made from buffalo milk

The following morning was our last in Luang Prabang, and I once again beat the sunrise—and my parents—to the morning market, where I enjoyed another delicious bowl of khao soy, savoring every sight and smell and sound of my surroundings, promising myself that I would not wait another four years to return.

If you’re getting tired of seeing infinite bowls of khao soy, then you’ve come to the wrong place

The world is a big place, and the more I see of it, the more I want to see. I’m constantly planning trips to new destinations, eager to experience more, do more, be everywhere.

Early next year, I’m hoping to finally hit my sixth continent with a trip to Australia and New Zealand. But as I plot out another uncharted adventure (and one that will eat up a large chunk of my vacation days for 2024), a voice in the back of my head is quietly nagging me: what about Laos? Can you survive another year without it? It’s only been five months, and you’re already itching and aching. Can you really endure another year and a half before your next return?

You see, as much as I crave novelty and the unknown, Laos—and Luang Prabang in particular—keeps calling me back. I long for those misty mornings on the banks of the Mekong.

Last week, on my walk to the gym, I caught a whiff of wood smoke, coming from god-knows-where. For just a brief moment, I closed my eyes and imagined that it was burning under a pot of or lam, tried to invoke in my mind the scent of chili wood and lemongrass, tried to feel the closeness of the morning fog.

In some ways, Luang Prabang will ruin you. It will leave you pining. It will have you engaged in the kind of magical thinking that is characteristic of loss and mourning—because as long as you’re away, you’ll feel its absence so profoundly that it will manipulate and pull at your senses like a mirage in the desert.

Once you’ve found Eden, every inch of your soul will urge you back. Loss and nostalgia will start to feel one and the same.